Tracing Light in a Virtual World

Boy it sure has been a while since I’ve written a blog post! Apologies for that.

I’m still working on The Halfling Project, with the newest project being Physically Based Rendering. I tried to implement environment maps in order to have specular reflections, but I got frustrated. So, I decided put The Halfling Project aside for a bit and try something new, specifically, Path Tracing.

I had a basic idea of how path tracing worked:

- Fire a crap-load of rays around the scene from the eye.

- At each bounce, use the material properties to accumulate attenuation

- If the ray hits a light, add the light to the pixel, taking into account the attenuation

Sweet. Now give me 2 hours and I’ll have the next Arnold Renderer, right?!? HA!

Ok. For real though. Googling pulled up lots of graphics papers and a few example projects. However, most, if not all of the graphics papers were advanced topics that expanded on path tracing, rather than explaining basic path tracing. (ie. Metropolis Light Transport, Half Vector Space Light Transport, Manifold Exploration Metropolis Light Transport, etc.) While they are really interesting (and some have example code), I felt they were way too much to try all at once. So, I was left with the examples I was able to find.

Example Projects

The first is smallpt, or more specifically, the expanded code/presentation done by Dr. David Cline at Oklahoma State University. Smallpt is true to its name, ie small. Therefore, as a learning tool, the reduced form is not very readable. However, Dr. Cline took the original code and expanded it out into a more readable form and created an excellent presentation going over each portion of the code.

The next example project I found was Minilight. It has excellent documentation and port to many different languages. It also has the algorithm overview in various levels of detail, which is really nice.

At this point, I realized that I had two choices. I could either implement the path tracer on the CPU (as in smallpt or Minilight), or on the GPU. Path tracing on the GPU is a bit of a recent advance, but it is possible and can work very well. So, being a bit of a masochist, and enjoying GPU programming thus far, I chose the GPU path.

The last extremely useful example project I found was a class project done by two students at The University of Pennsylvania, (Peter Kutz and Yining Karl Li), for a computer graphics class they took. The really great part, though, is that they kept a blog and documented their progress and the hurdles they had to overcome. This is extremely useful, because I can see some of the decisions they made as they added on features. It also allowed me to create a series of milestones in creating a project using their progress as a model.

For example:

- Be able to cast a ray from the eye through a pixel and display a color representation of the rays.

- Implement random number generation

- Implement an accumulation buffer

- Implement ray intersection tests

- Implement basic path tracing with fixed number of bounces.

- Implement Russian Routlette termination

- Implement ray/thread compaction

- Implement Specular / BRDFs

- Etc.

Choosing a GPGPU API

With a basic plan set out, my last choice was in the GPGPU programming API. My choices were:

- DirectX / OpenGL Compute Shaders

- CUDA

- OpenCL

I did quite a bit of searching around, but I wasn’t really able to find a clear winner. A few people believe that CUDA is a bit faster. However, a lot of the posts are old-ish, so I don’t really know how they stack up against newer versions of hlsl/glsl Compute Shaders. I ended up choosing CUDA, but Compute Shaders or OpenCL could probably perform just as well. I chose CUDA mostly to learn something new. Also, many existing GPU path tracing examples happen to be in CUDA, so it easier to compare their code with mine if I choose CUDA.

Off to the Realm of CUDA

First programs call for a “Hello World!” But how to do a hello world in a massively parallel environment? I mean, I guess we could write out “Hello World!” in every thread, but that’s kind of boring, right? So let’s store each letter used in one array, the offset to the letters in another array, and then calculate “Hello World!” in the threads. Now that’s more like it!

We only store the necessary letters. “Hello World!” is stored as indices into the character array.

char h_inputChars[10] = "Helo Wrd!"; uint h_indexes[13] = {0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 3, 6, 2, 7, 8, 9};

Then the kernel calculates the output string using the thread index:

__global__ void helloWorldKernel(char *inputChars, uint *indices, char *output) { uint index = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; output[index] = inputChars[indices[index]]; }

Yea, yea. Super inefficient. But hey, at least we’re doing something.

Ok, so now we know how to create the basic CUDA boilerplate code and do some calculations. The next step is figuring out how to talk between CUDA and DirectX so we can display something on the screen.

Bringing DirectX to the Party

Thankfully, the folks over at nVidia have made a library to do just that. They also have quite a few example projects to help explain the API. So, using one of the example projects as a guide and taking some boilerplate rendering code from The Halfling Project, I was able to create some cool pulsing plaid patterns:

Untz! Untz! Untz! Untz! Huh? Oh.. this isn’t the crazy new club?

Casting the First Rays

Ok, so now we can do some computation in CUDA, save it in an array, and DirectX will render the array as colors. On to rays!

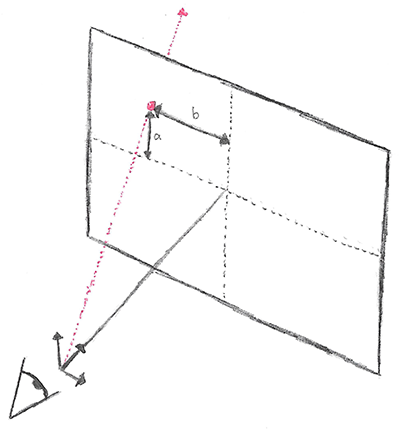

In path tracing, the first rays we shoot out are the ones that go from the eye through each pixel on the virtual screen.

In order to create the ray, we need to know the distances *a* and *b* in world units. Therefore, we need to convert pixel units into world units. To do this we need a define a camera. Let’s define an example camera as follows:

\[origin = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}\]

\[coordinateSystem = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 1 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]

\[fov_{x} = 90^{\circ}\]

\[fov_{y} = \frac{fov_{x}}{aspectRatio}\]

\[nearClipPlaneDist = 1\]

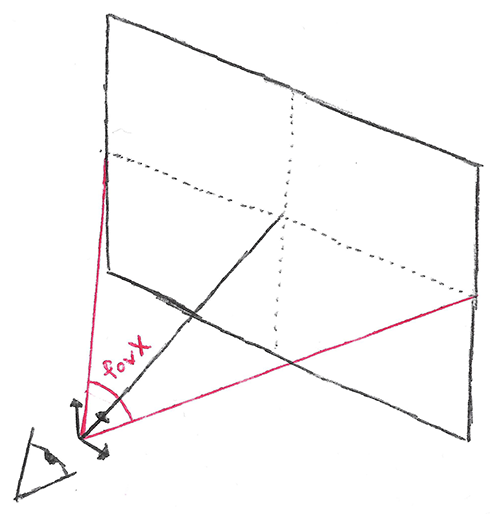

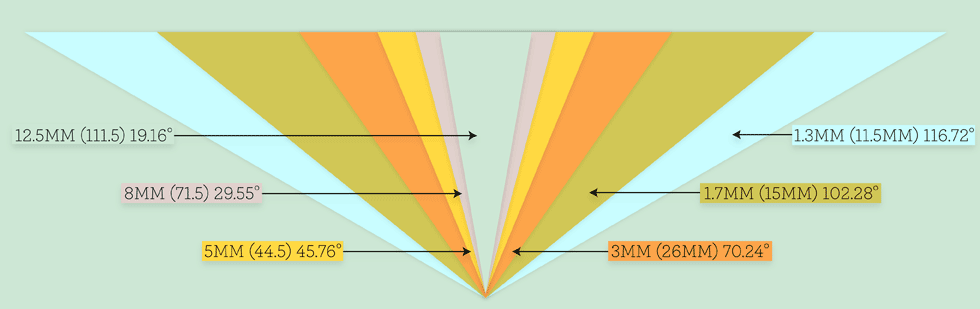

The field of view, or fov is an indirect way of specifying the ratio of pixel units to view units. Specifically, it is the viewing angle that is seen by the camera.

The higher the angle, the more of the scene is seen. But remember, changing the fov does not change the size of the screen, it merely squishes more or less of the scene into the same number of pixels.

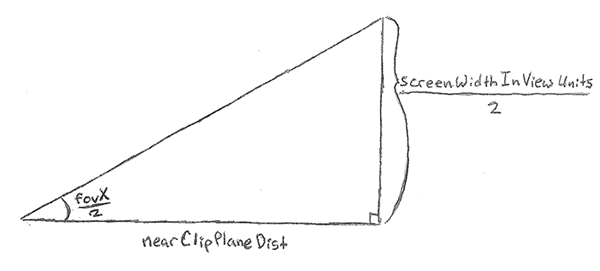

Let’s look at the triangle formed by fovx and the x-axis:

We can use the definition of tangent to calculate the screenWidth in view units

\[\tan \left (\theta \right) = \frac{opposite}{adjacent}\]

\[screenWidth_{view}= 2 \: \cdot \: nearClipPlaneDist \: \cdot \: \tan \left (\frac{fov_{x}}{2} \right)\]

Using that, we can calculate the view units of the pixel.

\[x_{homogenous}= 2 \: \cdot \: \frac{x}{width} \: - \: 1\]

\[x_{view} = nearClipPlaneDist \: \cdot \: x_{homogenous} \: \cdot \: \tan \left (\frac{fov_{x}}{2} \right)\]

The last thing to do to get the ray is to transform from view space to world space. This boils down to a simple matrix transform. We negate yview because pixel coordinates go from the top left of the screen to the bottom right, but homogeneous coordinates go from (-1, -1) at the bottom left to (1, 1) at the top right.

\[ray_{world}= \begin{bmatrix} x_{view} & -y_{view} & nearClipPlaneDist \end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix} & & \\ & cameraCoordinateSystem & \\ & & \end{bmatrix}\]

The code for the whole process is below. (In the code, I assume the nearClipPlaneDist is 1, so it cancels out)

__device__ float3 CalculateRayDirectionFromPixel(uint x, uint y, uint width, uint height, DeviceCamera &camera) { float3 viewVector = make_float3((((x + 0.5f) / width) * 2.0f - 1.0f) * camera.tanFovDiv2_X, -(((y + 0.5f) / height) * 2.0f - 1.0f) * camera.tanFovDiv2_Y, 1.0f); // Matrix multiply return normalize(make_float3(dot(viewVector, camera.x), dot(viewVector, camera.y), dot(viewVector, camera.z))); }

If we normalize the ray directions to renderable color ranges (add 1.0f and divide by 2.0f) and render out the resulting rays, we get a pretty gradient that varies from corner to corner.

Well, as this post is getting pretty long, I feel like this is a nice stopping point. The next post will be a short one on generating random numbers on the GPU and implementing an accumulation buffer. I’ve already implemented the code, so the post should be pretty soon.

After that, I will start implementing the object intersection algorithms, then the path tracing itself! Expect them in the coming week or so!

The code for everything in this post is on GitHub. It’s open source under Apache license, so feel free to use it in your own projects.

As always, feel free to ask questions, make comments, and if you find an error, please let me know.

Happy coding!